News articles, commentaries, reviews, translations on subjects of potential interest to progressive minded individuals and organizations, with a special emphasis on the Quebec national question, indigenous peoples, Latin American solidarity, and the socialist movement and its history.

Friday, December 16, 2011

Québec solidaire struggles to define its space in shifting political landscape

MONTRÉAL – About 400 members of Québec solidaire met here December 9-11 in a delegated convention to debate and adopt positions on major social and cultural questions. The convention capped the third phase in a lengthy process of developing what the left-wing sovereigntist party describes as a program of social transformation.[1]

Only days earlier, the QS candidate had tripled the party’s vote in a by-election in Bonaventure, a rural riding in the Gaspé region; her 9% of the popular vote (up from 3% in the 2008 general election) has inspired high hopes in the party of equivalent or better results in a Quebec general election, which could occur next year. A wave of enthusiasm swept the delegates when the candidate, Patricia Chartier, was introduced. Although she ran third (behind the Liberals, 49%, and Parti Québécois, 37%), her tally seemed to many a successful result for a small pro-independence party that is generally portrayed in the mass media as anti-capitalist.

Election expectations were definitely in the air as delegates turned their attention to education, healthcare, social welfare, housing and cultural and language policy. These are the bread-and-butter issues on which the party hopes its proposals will resonate with an electorate fed up with neoliberal austerity, cutbacks, downsizing and offloading. And they are issues with which many of the delegates are well acquainted through their own lives as teachers, students, healthcare professionals and workers, and activists in the various social movements.

The common theme of most of the adopted proposals was defense of existing public services and their accessibility free of charge in opposition to the wave of privatizations that is ravaging such services as healthcare and education. But delegates also adopted a resolution proposed by QS members in Jean-Lesage riding (Quebec City) calling for “democratic management of public services” through mechanisms of participative democracy allowing users, workers and local citizens to determine local and regional priorities and the resources to be allocated to them.

The delegates reaffirmed Québec solidaire’s commitment to free-of-charge public education from kindergarten to university. They called for strengthening “a public, democratic, secular school system independent of market forces.” However, by a large majority they turned down a proposal for a single public school system, voting instead in favour of a mixed system comprising both public schools financed by the state and private schools offering equivalent curriculum but without state funding. Some 20 percent of Quebec elementary and secondary students attend private schools, which are funded at present by the government. Thus, while wealthy elites may still send their children to private schools, the effect of the adopted proposal would be to stream many students into the public system.

The adopted resolutions also called for an end to shaping the curriculum of junior colleges (CEGEPs) to the job market and the interests of big business, and for freeing university research and development from corporate influences. Schools would be encouraged to propose their own curriculum, democratically decided in consultation with parents, students and staff, in addition to the official program of the Ministry.

The proposals on healthcare reflected an approach that would focus on preventive medicine and greater attention to alternative and traditional medicines. Proposed measures include strengthening front-line services in the popular local community service centres (CLSCs), enhancing home-care and restoring the public educational role of the CLSCs. A major issue is the lack of doctors in rural areas and remote regions. But delegates rejected a proposal that would impose financial penalties on doctors who leave Quebec before working five years in a region (10 in a university health centre). And on a very close vote they rejected a proposal to integrate all family doctors in CLSCs, which would effectively put them all on salary instead of fee-for-service.

A major issue in Quebec is the urgent need to strengthen French as the common language of employment and public discourse. Delegates voted for revisions to the Charter of the French Language (Law 101) that would, among other things, prohibit employers from requiring knowledge of English unless it is demonstrated that English is indispensable to the job, and to strengthen French as the language of work by extending the Charter’s reach to companies with fewer than 50 employees (the current threshold). They rejected proposals to make French the sole language of instruction in the CEGEPs and universities, reflecting QS’s position that students who wish to study in English do so primarily because of job requirements and that the solution lies instead in reinforcing French in the workplace.

A separate resolution was adopted on “Immigration and the French language.” It outlined how recent (and often non-Francophone) immigrants could be encouraged to integrate with the French-speaking majority through such measures as increased accessibility to regulated trades and professions, affirmative hiring of immigrants in the public service, and an end to job discrimination by ethnic profiling.

On media and communications, adopted proposals included creating a Quebec public radio network, eliminating commercial advertising on public radio and TV, and creating an independent agency to supervise and regulate Quebec broadcasting (replacing the federal CRTC). A major debate occurred over the proposal to “place distribution of telecommunications under public control, including if needed complete (100%) nationalization.” As one delegate noted, Quebec has the highest rates in the world for cell-phone use. In the end, however, the entire set of proposals on this topic was referred to the party’s policy commission for further study.

Proposals for substituting public debate and culture in place of commercial advertising and marketing in the media, and even “complete elimination of commercial advertising,” were set aside. Delegates instead called for regulations to avoid sexism, racism, violence, etc. from the media.

Québec solidaire is now on record in support of a guaranteed minimum income. In the context of a full-employment policy, the adopted resolution reads, “for anyone who is unemployed or with insufficient income, the state will provide a guaranteed and unconditional minimum income paid on an individual basis from the age of 18. This income could be complementary to income from work or other income support where these are below the established threshold.” This proposal should be read in light of previous QS commitments for a substantial increase in the minimum wage and for a shorter work week without reduction in wages. However, the “established threshold” was left undefined.

Delegates selected guaranteed annual income over other options that were proposed, such as a “citizenship income” that would operate like old-age security but be paid to everyone, children included; a living wage (salaire à vie) related to skills, studies, know-how, etc.; and a “universal guaranteed social income” that would replace all tax redistribution measures and income support transfers other than family allowances.

The convention also voted in favour of establishing a universal retirement plan comprising a vastly improved Quebec Pension Plan that would replace the many private and public plans, including RRSPs. Benefits would be defined and indexed, available at age 60, and adapted to need and years worked, with supplements for low-income beneficiaries. Employee contributions would be geared to capacity to pay.

Other proposals adopted included a massive program of investment in quality social housing (public, cooperative and community), and limits on rents to no more than 25% of income.

Finance capital gets a pass

While the delegates managed, on a very tight agenda, to wade through the 65-page resolutions book, readily disposing of a mass of detailed resolutions and amendments that had previously been debated in draft form in local membership assemblies and aggregates, they seemed less comfortable with some unfinished business that had been referred to this convention from the previous one in March for lack of time. These were resolutions on “Nationalization of the banks” and a similar one on other financial institutions, and a set of resolutions addressed to tax policy.

In the wake of the developing global protests against capitalist austerity and government bailouts of the banks, it might be thought that expropriation of the banks and financial interests would be high on the agenda of a party that sometimes promises to “go beyond capitalism.” And indeed, in the lead-up to the March convention, the QS policy commission had proposed, in a draft resolution, that “to eliminate completely the influence of private financial power,” an independent Quebec would implement “a complete nationalization of the banking system.” The QS national coordinating committee (CCN) had responded, however, with a counter-proposal to nationalize banking “if and as needed,” this phrase (au besoin) being underlined in the resolutions booklet.

But many of the delegates at this December convention were relatively new to the party, and seemed less familiar than those in the previous convention with economic and financial questions. Also, the left-over resolutions attracted little attention in the pre-convention discussions. And this convention met in a context that was much more electoralist-oriented; QS is now an established party, much more subject to media scrutiny and criticism. (This was the first QS convention covered live by Radio-Canada television.) Opportunist pressures weigh more heavily on the members.

No less than seven options were presented and debated. Most advocated “socializing” or “nationalizing” banking and private finance (one called for complete expropriation). In the end, the convention, voting each proposal up or down in a process of elimination, simply opted “to establish a state bank, either through creation of a new institution or by partial nationalization of the banking system,” which would “compete with the private banks.” As a few delegates had noted, however, as long as most of the banking and financial industry remains privately owned, a single bank could compete with others only on much the same terms; Quebec has a vivid example of this in the caisses populaires, the credit unions that started as a chain of small parish-based banks but now comprise the giant Desjardins complex which largely replicates the lending and investment practices of the major chartered banks.

The proposals for “nationalization of financial institutions other than banks” were referred without debate to the policy commission for further study. And the proposals on taxation policy were referred once again to the policy commission for consideration when preparing the QS election platform. These draft proposals included placing personal incomes 30 times the minimum wage in the highest tax bracket, imposing estate taxes, shifting the tax burden from individuals to corporations, and reviewing consumption taxes as “regressive.” (In its 2008 election platform, QS called for abolishing the Quebec sales tax or at least adjusting it to meet ecological concerns.)

All said, it was hardly “a program of social transformation,” as alleged by one enthusiastic QS member. But the adopted proposals are probably a fair representation of many of the demands raised by the social movements in current struggles, and enough to distinguish Québec solidaire, as an independentist party, from the capitalist Parti Québécois.

An end to discussion on program?

At a post-convention news conference, QS president Françoise David said the party “has now adopted almost the totality of the program that shapes our vision for the next 15 years.” She and other QS leaders now plan to convert a subsequent program convention, scheduled for April 2012, into a more modest event designed to fine-tune an election platform.

However, there are in fact many topics that have not yet been addressed in this programmatic exercise — among them, agriculture and international affairs. Québec solidaire originated amidst the mobilizations of the altermondialistes, the opponents of capitalist globalization, antiwar activists, and proponents of global justice and solidarity with progressive movements and governments around the world. David herself was best known for helping to initiate the World March of Women. The Union des forces progressistes (UFP), a QS predecessor, took strong positions in opposition to imperialist war and “free trade” agreements. These are positions that should resonate with the new generation of activist youth, “the indignés” who just recently occupied public spaces in Montréal and Quebec City in solidarity with the Occupy Wall Street movement.

It is worth noting, however, that QS does occasionally address international questions. An important initiative was taken this past summer when the QS leadership designated Manon Massé as the party’s representative on the Boat to Gaza project, in solidarity with Palestine and the Boycott, Sanctions and Divestment campaign unanimously endorsed at a previous convention. More such initiatives would be welcome.

Likewise, Québec solidaire has yet to develop its thinking on agrarian issues, or to connect in any significant way with farmers’ organizations that are fighting on behalf of “peasant agriculture” and organic farming practices. Some, such as the Union paysanne (UP), the Quebec affiliate of Via Campesina, are trying to abolish mandatory membership in the government-backed farmers organization, the Union des producteurs agricoles (UPA), which is dominated by major agribusiness interests. An agrarian program must be an integral part of any regional development strategy, and intersects closely with important environmental protest movements, including the mass movement now developing against shale gas exploration and development.

Another major area of Québec solidaire’s activity that remains largely undeveloped so far is the labour movement. Although the party adopted strong proposals on labour and trade unions at its March 2011 convention, it still lacks a consistent and coherent intervention in this milieu. A book recently published by QS leader Françoise David[2] outlining her vision for the party and Quebec scarcely mentions the organized labour movement or employment issues, although full employment and strong unions are key to achieving any serious redistribution of wealth in a capitalist society.

This lacuna has important implications for contemporary politics. The Charest government, taking advantage of recent exposures of corruption and union coercion in Quebec’s construction industry — and hoping to distract public attention from its own share of recent corruption scandals — has scapegoated construction workers by introducing legislation to abolish a longstanding practice of “placement syndical,” the union hiring hall by which jobs are allocated under the control of the respective unions the workers have chosen to represent them. Under Bill 33, workers will now be assigned to jobs by a government bureaucracy — unelected and not answerable to the workers. The main beneficiaries of Bill 33 will be the construction bosses, the very ones at the source of the industry’s corrupt practices. Yet Amir Khadir, the sole QS member of the National Assembly, did not fight the bill and was absent for the vote, when the 99 MNAs present voted unanimously in favour. A remarkable opportunity was lost for Québec solidaire to stand out as the sole defender of an important section of the Quebec working class.[3]

During a break in the convention proceedings, about 30 members, mostly trade unionists but also a few students, met in a meeting of the party’s “Intersyndicale,” an informal caucus of union members, to discuss ways to network and engage in possible future actions, especially in collaboration with student activists who are mounting a militant campaign for free education in opposition to the Charest government’s scheduled tuition fee increases. The Intersyndicale has recently published an attractive leaflet outlining the program on labour and the unions that was adopted at the March 2011 convention.

Major challenges ahead

Québec solidaire faces some imposing challenges in the coming period. The tectonic plates under Quebec’s political landscape are shifting. The capitalist parties that have dominated the province’s politics for the last 40 years or more are in crisis. Jean Charest’s governing Liberals (the PLQ) are mired in mounting scandals, and popular discontent with the party is fueled in particular by its flagrant collaboration with the resources multinationals; yet Charest’s new flagship program Plan Nord offers only further concessions to them. The Parti québécois, out of office since 2003, is bleeding profusely from the crisis that erupted in sovereigntist ranks on the heels of the New Democratic Party’s “orange surge” in the May federal election. To date, a half-dozen of its MNAs have defected, most of them in opposition to PQ leader Pauline Marois’ insistence on placing the fight for Quebec sovereignty on the backburner for the foreseeable future.

Meanwhile, a group of former Péquistes and Liberals led by ex-PQ minister François Legault and businessman Charles Sirois have formed a new party, Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), which advocates putting the national question on ice for the next ten years — a position which apparently appeals to many Québécois who have abandoned hope for any change in Quebec’s constitutional status for the foreseeable future. The CAQ has already absorbed the right-wing Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ) and appears to be capturing substantial support from former Liberal and PQ supporters although it has yet to contest any election.

Québec solidaire is faced with an unprecedented opportunity to mobilize support among disaffected Péquistes as the independentist party with a relatively progressive social agenda. However, under the first-past-the-post electoral system, its electoral prospects are quite uncertain, and in a multiparty context it is impossible to predict how even an electoral score of 10% or more might — or might not — translate into seats in the National Assembly. In the circumstances, the party leadership — and a portion of the membership[4] — continues to entertain hopes of negotiating a deal with the PQ (or possibly the Verts, the “Green” party) under which each party would agree to stand down from running a candidate in one or more ridings where the two parties are in relatively close contention, thus facilitating the election of QS candidates. Many QS members are inclined to view the PQ as a party of the “left” — not so much because of its politics, which are thoroughly neoliberal, but because QS and the PQ appeal to much the same constituency of working class voters.

In recent months both Françoise David and Amir Khadir, the party’s co-leaders, have publicly spoken in favour of such a deal, to the dismay of many QS members, who voted at the party’s last convention in March to reject any such “tactical alliances.” With this in mind, QS militant Marc Bonhomme moved an emergency motion at the opening of the QS convention to add to the agenda a debate on the question of alliances, from the perspective of proposing that QS work instead to build a “left front,” both electoral and extra-parliamentary, with the unions and popular movements “against the Right of the banks, the bosses and the parties in their pay, the PLQ-PQ-ADQ-CAQ.” Bonhomme’s motion was defeated. Although the vote meant there was no debate on the strategic direction for QS proposed by the motion, it does mean that the March convention’s decision remains in force — as Amir Khadir later conceded to reporters who had been unaware of the vote taken in March in a closed session of that convention.

In any event, the PQ has virtually ruled out any talk of alliances. In a document on institutional reform to be debated by its National Council in January, the PQ leadership opposes any electoral reform that would offer proportional representation to parties (as proposed by Québec solidaire), and proposes instead a two-round system of voting in which, failing a majority for a candidate in the first round, the two candidates with the highest scores would face off in a second round. Given its present standing in the polls, Québec solidaire’s candidates would have little chance of election except in a very few Montréal ridings under this formula.

Still unclear is the possible long-term impact on Québec solidaire of the recent gains of the NDP, now a factor in Quebec politics and not just on the federal scene. Notwithstanding QS’s independentism, there is considerable overlap in popular support and even membership of the two parties. Significantly, the QS candidate in the Bonaventure by-election, Patricia Chartier, staffs the constituency office of the local NDP member of parliament. However, the NDP’s progress in Quebec may be ephemeral; judging from recent opinion polls, its stumbling on some issues related to the national question during the recent session of the federal Parliament — such as its acquiescence to the appointment of a unilingual Anglophone Supreme Court judge and federal Auditor General, or its contradictory reactions to Quebec’s exclusion from the recent multibillion dollar shipbuilding contract — is a factor in a serious decline in support in the province. The NDP’s historic inability to relate to Quebec’s national consciousness is demonstrated repeatedly, even on questions that may seem trivial to an uncomprehending audience in English Canada but are regarded by most Québécois as vital to their identity and existence as a minority nation within Canada.

Richard Fidler, December 16, 2011. Thanks to Nathan Rao, like me an observer at the convention, for his input.

[1] For reports on previous program conventions, see “Quebec left debates strategy for independence” and “‘Beyond capitalism’? Québec solidaire launches debate on its program for social transformation.”

[2] F. David, De colère et d’espoir (Montréal: Ecosociété, 2011).

[3] For an excellent analysis of the issues raised by Bill 33, and a critique of Québec solidaire’s silence on the matter, see “Comment comprendre l’abolition du placement syndical dans l’industrie de la construction?” by André Parizeau, the leader of the Parti communiste du Québec, a recognized collective within QS.

[4] See, for example, “Québec solidaire et les pactes tactiques : un mal nécessaire.” The author, Stéphane Lessard, is a former member of the QS national coordinating committee, the party’s top leadership body.

Friday, November 11, 2011

Massive protest in Quebec against huge hike in tuition fees

The students were joined by smaller but significant contingents from some unions and other social movements. Marching with them were professors, teaching assistants and support staff. The university rectors and principals characterize the steep increase in fees as “reasonable,” and say it will be compensated for students from low-income families by increased loans and bursaries. The students point out, however, that it will only aggravate their indebtedness. “Eighty percent of the students are without access to financial assistance,” says Léo Bureau-Blouin, president of the Fédération étudiante collégiale du Québec (FECQ). “Once a family makes $60,000, it is no longer eligible.”

Further actions are being planned, student leaders report. With the support already of about 10 Quebec student associations, an unlimited general strike could well take place this winter if the government does not retreat, Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, a spokesman for the Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante (ASSE), told Le Devoir. “This was the final warning for the Charest government.”

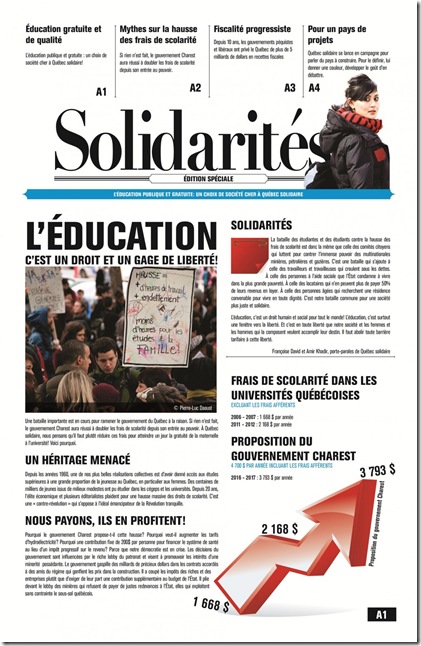

Québec solidaire (QS), which had a large contingent in the Montréal demo, published a four-page tabloid newspaper for distribution to the student demonstrators. It featured the party’s call for “free tuition from kindergarten to university” and an “end to public financing of private schools.” Here is its front page:

Addressing the demonstrators on behalf of Québec solidaire, Amir Khadir (the QS member of Quebec’s National Assembly) pointed to some of the alternative sources of revenue that might be used to pay for higher education: royalties on industries and business for their use of water, considered a “loaned” public property; increased royalties on mining production; restoration of capital taxes for financial firms; and increased taxes on the richest individuals. “He can go and find 5 billion dollars with these measures,” said Khadir. “Why choose, out of ideology, to ignore that?”

However, notes QS activist Marc Bonhomme, neither the QS tabloid nor Khadir indicated how they proposed to fund free education, let alone the massive reinvestment in health, public transport and energy efficiency that is also needed.

The colourful, enthusiastic demonstration in Montréal, says Bonhomme, showed that this demo was not the traditional trade-union “heroic last stand” before capitulation, or a safety valve with no follow-up. This was something new, as the students loudly demonstrated when some speakers raised the possibility of a general strike.

November 11, 2011

Thursday, September 29, 2011

Ottawa tar-sands protest: reports and impressions

I participated in the demonstration against the Alberta tar sands outside the Canadian Parliament here in Ottawa on September 26. As was widely reported, the civil disobedience component of the action resulted in over 200 arrests.

I am cross-publishing here two accounts of the day’s events that are much more informative than what appeared in the corporate media. And I follow them with some of my own thoughts about the action.

* * *

Sit-in protests Keystone XL pipeline

Civil disobedience on Parliament Hill results in more than 200 arrests

by Julie Dupuis, for Straight Goods News

(Cross-posted with permission)

OTTAWA, September 27, 2011, Straight Goods News — Nearly a thousand people gathered Monday on Parliament Hill in front of the Centennial Flame to protest the Keystone XL pipeline, which would transport tar sands crude oil to Texas. Organized by the Council of Canadians, Greenpeace Canada, and the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN), the solidarity rally drew participants ready to risk arrest, by attempting a sit-in in the Centre Block or by supporting those engaging in civil disobedience.

Before the main event, several high-profile speakers addressed the crowd. Clayton Thomas-Muller, indigenous tar sands organizer for the IEN, kicked off the event by thanking the Algonquin First Nation for use of the “unceded land” on which lies the parliamentary buildings. First Nation Elder Terry McKay then led the gathering in prayer to the Creator, followed by a drum song.

“Justice!” resounded all around as, to fire up the crowd, Thomas-Muller called, “What are we here for?”

Chief Bill Erasmus of the Dene First Nation and the Assembly of First Nations took the podium, pointing out that people who live downstream from tar sands tailings ponds are dying of cancer.

“Shame!” cried the protesters.

Chief Erasmus noted that it takes four to five barrels of water to produce one barrel of oil.

“Shame!”

Chief Erasmus claimed that Canada’s goal is to become the #1 producer of oil.

“Shame!”

He said private landowners are concerned about cleaning up spills and that the original Keystone pipeline, operated by the same company that would operate the new proposed pipeline, has had twelve spills in the last fourteen months.

“Shame!”

Chief Erasmus concluded with an appeal to President Obama, who will decide next month whether to approve or reject the Keystone XL pipeline: “Obama, come up with a new sustainable way to deal with fossil fuels. We need your help.”

David Coles, President of the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada (CEP), said about the pipeline, “It’s a no-brainer and Harper’s got no brains.”

Dispelling greenwashing claims, Coles asked, “What blooming idiot came up with the idea of ‘ethical oil’?”

Chief Jackie Thomas of the Sai-kuz First Nation attended the event as a symbol of solidarity. Her tribe is battling not the Keystone XL pipeline, but the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline, which would transport tar sands oil from Alberta to BC’s coast. Her message to Enbridge: “Don’t try us.”

Lionel Lepine, lawyer for the Athabasca Chipewyan Dene Nation, said, “They call it the House of Commons. I don’t see any common sense in there.” Lepine said his community is suffering tremendously from tar sands development, its people dying of cancer and other illnesses. The documentary H2Oil demonstrates its plight.

“I vow until my dying breath to continue this fight,” finished Lepine.

Representing Greenpeace Canada and the Lubicon Cree First Nation, Melina Laboucan-Massimo said her family is also ill, but from the Albertan oil spill that was left unreported for five days last spring, until the federal election had passed. Her voice quivered at times as she enumerated her relatives’ symptoms, lamenting that a few individuals are profiting from their pain. Echoing Lepine, Laboucan-Massimo asserted, “This behind me is the House of Commons, not the House of Corporations.”

Former Senate page Brigitte DePape was there representing the Youth Climate Justice Coalition, which DePape revealed is organizing a tribunal to put the Harper government on trial. “This is where change is happening,” DePape told the protesters, saying she was happy to be standing with them and “not in there”, pointing behind her to Parliament. DePape’s parting message was to “organize together for another possible Canada”.

Council of Canadians chairperson Maude Barlow referred to an imaginary map depicting current and proposed pipelines, and said, “It looks like a corporate snakes and ladders board game.”

“In my opinion,” said Barlow, “the people crossing the line today are not breaking the law. The people breaking the law are the Harper government.” Barlow cited the Fisheries Act, the Kyoto Protocol, the UN Declaration on the Human Right to Water, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“Today we stand on the face of change,” Thomas-Muller had told the crowd.

Sit-in participants lined up behind police fences and, in waves of six people, they crossed the fence to be arrested. The first to cross were Maude Barlow, George Poitras, former Chief of the Mikisew Cree First Nation, Dave Coles, Tony Clarke, Director of the Polaris Institute, and Elizabeth Bernstein of the Nobel Womens’ Initiative, among others.

Also in attendance at the rally were Green Party of Canada leader Elizabeth May and Dennis Bevington, NDP MP, Western Arctic. Charlie Angus, NDP MP, Timmins-James Bay, appeared to show his support around three o’clock, while Stéphane Dion, Liberal MP, St-Laurent–Cartierville, arrived at 9 a.m.

More than 200 people were arrested for trespassing, fined between $55 and $75, and banned from Parliament Hill for one year.

Opponents of the Keystone XL pipeline say the project violates First Nations Treaty Rights. It threatens food and water supplies because it crosses the Ogallala Aquifer, the world’s largest known underground lake, as well as countless farms. The project takes jobs out of Canada and contributes to added tar sands pollution, increasing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere.

As Dave Coles asked the crowd amassed in front of the Centre Block, “What about energy security for Canada?”

Thomas-Muller gave participants hope that positive change is forthcoming. “This is who we are,” he said, “but this is not who we will continue to be.”

Julie Dupuis holds an MA in English Literature from the University of Toronto (2005) and did post-graduate work in Creative Book Publishing at Humber College (2007). She has been writing for a living since 2006, has published four travel articles, and is the Associate Editor of Public Values.ca and Valeurspubliques.ca. She is an avid hiker and traveller.

eMail: julie@straightgoods.com. Web: http://juliedupuis-naturalnomad.com/.

* * *

Over 200 arrested at Ottawa tar sands protest

By Marco Vigliotti | September 27, 2011, rabble,ca

Over 200 protesters objecting to the federal government’s enthusiastic support for Alberta’s tar sands and the Keystone pipeline XL were arrested Monday morning as they attempted to stage a sit-in in the House of Commons.

The protesters wanted the chance to air their grievances with the environmentally reckless policies of the Harper-led Conservatives inside Parliament but were blocked from entering by fenced barricades and over 50 RCMP officers.

The protesters were encouraged by hundreds of boisterous supporters as they passed the media scrum and calmly hopped over police barricades.

Those arrested in the first wave of protesters trying to gain access to the House included chairperson of The Council of Canadians, Maude Barlow, and Dave Coles, the president of Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union, along with his executive assistant and rabble.ca blogger Fred Wilson.

Organizers want to deliver a strong message denouncing the Conservative government’s support for the Keystone XL pipeline and continuing tar sands development.

“We’re here today in solidarity with the multiple other NGOs, unions and every day citizens who decided to send a very united direct message to the Harper regime that we will not stand for this anymore,” said rally organizer and tar sands campaigner for the Indigenous Environmental Network Clayton Thomas-Mueller.

“We want energy justice, we want a zero carbon energy economy that doesn’t sacrifice certain communities for the benefit of shareholders of big private oil companies living thousands of miles away.”

No incidents of violence were reported and both sides in the rally behaved civilly, to the point that police placed a small step ladder on the far side of the barricade for protesters to safely descend.

“I think the police have conducted themselves in a peaceful way,” said Thomas-Mueller. “Their decision to only charge folks with trespassing versus a criminal charge, we definitely appreciate that.”

Thomas-Mueller noted the stark contrast of this peaceful protest with the turbulence of recent police and activist confrontations.

“This is a very welcome exchange from what we’ve seen in the G-20 and the Olympic mobilization where police definitely were a lot more hostile” says Thomas-Mueller, “so today was a good day.”

A diverse group of speakers kicked off the protest rally sharing their own personal stories of suffering from the colossal impact of the Alberta tar sands.

Chief of the Dene Nation, Bill Erasmus, spoke of the struggle that his community, which is 800 miles downstream of the tar sands, faces with water contamination and pollution.

“There are tailings ponds that total 700 square miles of toxic waste, that waste goes into the water system, we are downstream we feel it,” Erasmus said. “[Former Chief of the Mikisew Cree First Nation] George Poitras spoke of members in his community dying of cancer, we’re only a couple of miles downstream from them and we’re starting to feel it.”

“Canada wants to become the number one world producer of oil at our expense,” added Erasmus.

“It was a changed landscape forever,” said Melina Laboucan-Massimo, Climate and Energy campaigner for Greenpeace Canada about her Lubicon Cree community’s struggle with the Rainbow Oil pipeline leak this past spring.

“It consumed a whole stretch of our traditional territory, where my family once hunted, once trapped, once picked berried, once harvested medicine for generations and can no longer do it,” added Laboucan-Massimo.

The speakers shared a sense of frustration of being ignored by the Conservative government despite the scientific evidence and strong opposition against tar sands development.

“It is simply wrong to poison the fish and wildlife which indigenous people living downstream depend on for their livelihood thereby causing unprecedented high incidents of rare cancers in First Nations community, it is dead wrong,” Tony Clarke, the director of the Polaris Institute, said.

“The Harper government has taken its marching orders from Big Oil and has effectively shut out the voices of civil society.”

Communications, Energy and Paperworkers (CEP) Union president Dave Coles denounced the Harper government as foolish and incompetent for their Keystone pipeline projects.

“How the hell do you de-link jobs, the environment, the economy, First Nations rights? You can’t, it’s a package and you can’t put it in a pipe and ship it to Texas,” charged Coles. “Stephen Harper’s right, it’s a no-brainer -- and he has no brains.”

Many in the crowd spoke of the need to fight back against the continued development of the tar sands by coming together and strengthening the opposition movement.

“This rally is about bringing a common voice recognizing that the government is ignoring opposition to the tar sands development,” said Andrea Harden-Donahue, the Energy and Climate Justice Campaigner Council of Canadians, “The stronger our movement is the more power we will have.”

With the Conservatives controlling all levers of power in Ottawa, renegade page Brigitte Depape urged activists to use civil disobedience to oppose the Harper government.

“We have tried institutional means and they have failed, and we know change won’t happen in Parliament and we know it won’t happen from writing policy reports,” Depape said. “Change happens when we take action. We may not have the money and resources that government and companies have but we have people power.”

Marco Vigliotti is an Ottawa-based freelance journalist.

* * *

From witnessing to strategy?

A few brief comments of my own on some aspects of this action.

From the outset, the demonstration was explicitly designed to be “one of the largest acts of civil disobedience on the climate issue that Canada has ever seen.” Both the political message and the tactic to convey it were described by the organizers:

“Our goal is very simple: to peacefully and responsibly go through the main doors of Parliament to the foyer of Centre Block and sit-down so we can deliver our message: All people in Canada deserve a clean energy future that promotes climate justice, where Treaty and Indigenous rights are respected and the health of our communities and the environment are prioritized. To secure this for future generations we must turn away from the toxic tar sands industry and oppose Harper's reckless climate agenda.

“We are asking each person to make a personal commitment, to weigh all the factors and if you feel it is appropriate, to join with people from across the country in a peaceful, arrestable civil disobedience action on Parliament Hill.

“This is our objective: to enter the house of the people and send our message of hope for the future.”

Predictably, the tactic had to be radically amended. Only a huge mass movement linked in action to sympathizers working inside the building could hope to storm and occupy this holy of holies of Canadian representative democracy. The police foreclosed the plan by erecting a four-foot (1.3 metre) metal fence in front of the steps to the Parliament, with an additional 8 foot metal barrier at some distance behind the first fence — completely shutting down public access to the building. The Commons was closed to the commons.

Nevertheless, as a statement of moral protest against the environmental destruction of the tar sands, I think the action can be considered a modest success.

Maude Barlow of the Council of Canadians explains the thinking behind the action:

“I took part in the two week rolling protests held in Washington in late August.... I was deeply moved by the dignified process of non-violent civil disobedience I witnessed there and vowed to help create a similar event in Canada.

“So with Greenpeace, the Indigenous Environmental Network, the Polaris Institute, and the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union (who represent the tar sands workers), the Council of Canadians organized a similar demonstration of civil disobedience and worked with local police forces to make it as dignified and peaceful as possible.

“Over 800 Canadians gathered on the Hill, where we heard the stories of despair from First Nations people living downstream of the tar sands and the need to take our campaigns to the next step of direct action....”

This “direct action” of “civil disobedience” was by its very nature addressed to those already convinced of the enormous danger and destruction posed to humans and our environment by the tar sands operations and determined to manifest their opposition in dramatic fashion. It was designed essentially as a media spectacle, the mass arrests, that would startle public opinion and perhaps stimulate thinking in broader layers about why so many people were prepared to be arrested in this cause.

As Barlow explains, for her — and no doubt for many of the demonstrators — “It was not an easy decision to make.

“The charges could very well have been criminal and impair my ability to do work in the United States, which would have been devastating for me. I chair the board of Food and Water Watch in Washington and serve on advisory boards of several other organizations. I also speak to many American groups and at universities. The merging of the no-fly lists between Canada and the United States is a real and growing concern, as many of us fear such lists will be used to shut down peaceful dissent.

“But the day comes when you have to take a stand beyond the range of your comfort zone and for me, this was the day. I have four grandchildren I love more than life itself and I want them and all children to grow up in a safe and healthy world. I was lucky to have on one side Dave Coles, the fearless president of the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union and on the other, Fred Wilson, senior adviser to Dave and a wonderful board member of the Council of Canadians....”

As it happened, the police had decided in this instance not to employ the tactics they have so readily used in some recent protests such as the G20 demonstrations in Toronto in 2010. Instead, they turned the potential confrontation into a peaceful pantomime. But, as Barlow reminds us, the outcome could easily have been much worse:

“I was asked three times by a very respectful police officer to go back over the fence and when I refused, he arrested me for obstructing a police officer, a serious criminal charge. I was handcuffed, searched and escorted by an also respectful policewoman and sat, as did my friends, for a long time while they decided what to do with us. Finally, they thankfully decided on the lesser charge of trespassing and we, and the 200 others who followed us over the fence, were given a fine and an edict to stay away from Parliament Hill for a year....

“I realize that at no time was my life in danger as is the case for activists in some other countries or even some groups in our own. But I also for a short time, felt the unnerving experience of being totally and completely out of control of my life and it has left me shaken....”

However, Barlow concludes, she felt personally energized by the experience: “Mostly I feel privileged to have been part of a wonderful experience where people of all ages and from all over the country came together to put themselves on the line.”

Personally, I respect the commitment and dedication of those who engaged in this action. (Like the majority of the demonstrators, I chose not to go over the fence.) Theirs was a strong statement of personal witness, and may well have convinced many others to think more deeply about the issues.

And certainly, the action was a valuable opportunity for many activists from across Canada to connect with each other and establish links that will serve them well in future activities. On the day preceding the action, some 250 of us participated in a nine-hour training session at the nearby University of Ottawa that included a short teach-in on the issues, and group enactments of how to counter anti-climate propaganda and resist police intimidation. (There were few from Quebec, however, the province that has seen the largest environmental protests and mobilizations, most recently in opposition to shale gas exploration.)

Nevertheless, there were in my view some aspects to the action that also merit critical consideration.

An obvious one, to me at least, was the lack of any specific proposal for future action. Instead, the organizers are simply urging supporters to “take the pledge” — the pledge in question, published on their web site, being “to get involved in my own community to help build a clean green energy future where Indigenous rights are respected.”

Similarly, there is no proposal yet for a collective fight against the trespass charges. As the state’s response to the “civil disobedience” objective, these charges may be seen by some as a welcome confirmation of their success. In an email message today to the participants, the organizers say:

“We are currently consulting with lawyers to determine next steps for those who were arrested. At this point please feel free to deal with your [offence] tickets in any way you see fit. We will be communicating a follow-up legal strategy in the near future.”

Also worth noting, in my opinion, is a programmatic deficiency in some of the anti-pipeline agitation.

For example, although it was not publicized — and was even obscured by the organizers — not all of the participants agreed on the need to shut down the tar sands if not immediately, at the earliest opportunity, and to reorient the workers involved toward climate-sustaining employment.

The Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada (CEP) was the major union with a presence at the Parliament Hill action. It represents more than 35,000 workers in the oil, gas and chemical industry in Ontario, Alberta and several other provinces, including the tar sands workers in Alberta. But the union, while strongly opposed to the Keystone and other pipelines that export bitumen from Alberta, does not oppose the tar sands operations as such, although it opposes “additional oil sands development.” The union advocates a Canadian nationalist strategy of fighting to keep oil industry jobs in Canada and promoting “Canadian energy security.”

In a briefing note published by the CEP, the union lists its key demands:

- The Canadian government should not support the U.S. approval of Keystone XL....

- The Canadian government should develop a strategy to increase the bitumen upgrading and refining capacity in Canada.

- The National Energy Board must be compelled to consider the impact on job creation when licensing pipeline projects.

- The Canadian government should develop a national energy strategy that promotes energy security, environmental sustainability and job creation in Canada.

What the CEP shared with the other protesters in Ottawa on September 26 was opposition to the Keystone pipeline. In his speech to the rally, CEP president Dave Coles did not mention the union’s support for building refining capacity in Canada.

The CEP position is widely held in the Canadian labour movement. The Alberta Federation of Labour says Canada should “move up the value ladder with our oilsands resources, rather than sell our resources south of the border in their raw form.” The 2008 convention of the Canadian Labour Congress adopted a resolution on the tar sands which advocates:

- “Regulate” the Tar Sands to “protect the environment”

- “Minimize” the impact of Tar Sands on aboriginal communities

- Limit unrefined raw oil exports in favour of refining in Canada

- Declare a moratorium on “future” Tar Sands projects

- Support Indigenous peoples struggling against Tar Sands developments.

The New Democratic Party has a similar position. In this year’s federal election, the party said it would “encourage value-added, responsible upgrading, refining and petrochemical manufacturing here in Canada to maximize the economic benefits and jobs for Canadians.”

The NDP gave at best lukewarm support to the September 26 protest. Two or three of the party’s MPs circulated in the crowd (as did Green leader Elizabeth May), although no party representative was invited to speak. In a rather droll gesture, a single NDP MP, Dennis Bevington, was allowed by police to stand between the steel barriers in front of the Parliament building and applaud those who were climbing over the fence to be arrested.

To some degree, these contradictions could be glossed over at the September 26 protest, with its emphasis on the Keystone pipeline. As Maude Barlow puts it, in her article quoted above, “by investing trillions of dollars into these pipelines, governments and the energy industry are ensuring the continued rapid acceleration of tar sands development, instead of supporting a process to move to an alternative and sustainable energy system.”

But what would that process involve? There was really no mention at the rally of any strategy or concrete demands for massive conversion from fossil-fuel dependency to climate-friendly jobs in renewable resource-based industries — despite the clear message from the overwhelming majority of the speakers, in particular the indigenous leaders, who called for not just an end to tar sands exploitation but a radical rethinking of the relationship between humans and our natural environment.

Nationalist appeals that are effectively calls to “keep our climate-killing jobs in Canada” will not build the movement that is needed. It seems to me that there is an urgent need for the labour movement, the NDP, and environmental activists to find ways to develop a coherent alternative program to the program of the government and the oil companies.

In a recent speech to audiences in Australia, the Canadian climate blogger Ian Angus calls for “a new industrial revolution, a new energy revolution.” He adds: “We need to change what we make and how we make it. Entire industries need to be eliminated and others need to be transformed.” And he cites an encouraging initiative by some trade-unionists in Britain:

“One powerful example is in Britain, where trade unionists in the climate change movement are promoting a call for One Million Climate Jobs. Not just loosely-defined ‘green jobs’ that clean up the mess while leaving the causes untouched, but specifically climate jobs.

- Jobs building new energy sources and a new energy grid.

- Jobs retrofitting homes and offices for energy efficiency.

- Jobs expanding public transport and railroads.

- And more

“In their document calling for One Million Climate Jobs they have documented just what has to be done, and what it will cost. They have shown that it is possible, and affordable, and essential.

“This campaign takes the concept of a ‘just transition’ into new territory – not just protecting current income, but actually fighting for a union-initiated transition to a new kind of economy.”

It is proposals like these that should be discussed and developed within the unions and the climate-change movement as a whole with the objective of developing campaigns around specific energy and job-conversion projects.

Friday, September 23, 2011

The North, the Arctic and the Indigenous national question – A Québécois perspective

Introduction

In the September issue of the pro-sovereignty newspaper, L’aut’journal, editor Pierre Dubuc writes an interesting account of the geopolitics involved in the northern and Arctic development plans of the Canadian and Quebec governments, and spells out some of the implications for the Indigenous peoples who make up the majority of the inhabitants of these regions.

Dubuc concludes with a challenge to supporters of Quebec independence: Will they oppose the Inuit people as they assert their sovereignty claims, or “will they ally with the Inuit against the federal government, linking their struggle for the sovereignty of Quebec with that of the Inuit, within the framework of what could be a sovereignty-association?”

These are important questions for Québécois sovereigntists, who — like most Quebec and Canadian federalists — have often displayed indifference or even hostility to Indigenous struggles against capitalist “development” and for self-government and sovereignty of their territories and communities within the territory of present-day Quebec (Québec Solidaire is an exception in this regard.) The Parti Québécois leadership has historically devoted much greater attention to its hopes for association with capitalist Canada than it does to developing links of solidarity with the Inuit and the dozen or so other Indigenous nations formally recognized by the National Assembly in the mid-1980s.

Dubuc is a leader of a left-wing ginger group that campaigns for Quebec independence, although it still supports the Parti Québécois: Syndicalistes et progressistes pour un Québec Libre (SPQ Libre). L’aut’journal, which is funded in part by some Quebec trade unions, is widely read in Quebec. It is to be hoped that articles like this will help stimulate further discussion of these issues in Quebec’s nationalist, labour and left circles. The movement for Quebec independence can only succeed as a component of a much vaster emancipatory project.

Dubuc explains in a note attached to his article that much of the information he recounts is drawn from the recent book by Shelagh D. Grant, Polar Imperative, A History of Arctic Sovereignty in North America (Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 2010). Here is my translation of the major part of his article; I have added a few notes of my own for clarification, in places.

– Richard Fidler

* * *

The North, the Arctic and the Indigenous national question

by Pierre Dubuc

The Far North and the Arctic are increasingly important regions for the governments in both Quebec City and Ottawa. In Québec, the Charest government is making its Plan Nord the key to Quebec’s future economic development. In Ottawa, the Harper government is vastly stepping up its trips and initiatives, especially those of a military nature, to guarantee Canadian sovereignty over the Arctic.

The new importance of the Far North and the Arctic is a consequence of the melting of the glaciers, which opens the way to mineral and hydrocarbon development. Up to 20% of the world’s undiscovered reserves of gas and oil are buried in the Arctic soil. The warming of the Arctic also opens the Northwest Passage linking the Atlantic and the Pacific to international trade. It is calculated that a trip from Tokyo to London would be shortened by 14 days in comparison to the Suez and Panama canal routes, saving about a third in fuel costs. Charest’s Plan Nord provides for a deepwater port on Hudson Bay and the shipping of ore to Asia through the Northwest Passage.

Canada wants to affirm its sovereignty over the Arctic — a region that represents 40% of its territory and on which 110,000 persons are living — and more particularly over the Northwest Passage, while the United States, Europe and Asian countries consider it is an international strait linking two oceans.

The United States cannot accept Canada’s position because it could create a precedent for the strait of Malacca in Southeast Asia or the strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, but Washington understands that Canada cannot renounce its claims and is legally bound to ensure that the waters in question are used safely. The two countries have therefore reached an agreement not to agree.

That did not prevent the Canadian government from announcing in 2010 the purchase of a fleet of six to eight offshore patrol vessels at a cost of $9 billion, in addition to the $720 million for the future icebreaker John G. Diefenbaker and some military bases to supply these ships. Parallel to this, Canada plans to increase its Ranger force from 900 to 5,000 men under the command of the Northern Joint Task Force, and to supply them with state-of-the-art material and equipment including stealth snowmobiles.

Journalists and experts query the relevance of these expenditures, noting that Canadian sovereignty is not threatened by foreign countries. But more seasoned observers know that the threat exists and that it comes from within. The Inuit of Nunavut and Nunavik are following with great interest the evolution toward complete independence of their brothers and sisters, the Inuit of Greenland, now scheduled for 2021.

During a consultative vote in November 2008, 75% of the Greenlanders voted in favour of independence. The referendum reinforced their position in their negotiations with Denmark on self-government. In this regard, the preamble to the Danish parliament’s legislation on Greenland stipulates that “the inhabitants of Greenland are recognized as a people under international law, with the right to independence if they so desire after the holding of a referendum and negotiations with Denmark.” At present, the Greenland government holds all powers except over foreign policy, security, the Supreme Court and the coast guard.

Coveted territories

There is nothing new in this interest in the Far North and Arctic. They have been the scene of wars between France and Great Britain, and rivalries between Canada and the United States. It is significant that the treaty for the purchase of Alaska from Russia by the United States was signed on the very same day [in 1867] that Queen Victoria placed her signature at the bottom of the British North America Act. In 1869, the United States was also thinking of purchasing Greenland and Iceland with the goal of acquiring the Arctic lands claimed by Canada.

It was under the governments of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (1896-1911), but mainly Pierre-Elliott Trudeau (1968-1984), that Canada sought to secure its sovereignty over the Arctic — the United States, in the latter case, having taken advantage of two world wars and the Cold War to install its radio and radar stations and airports in the Arctic.

Under Laurier, Senator Pascal Poirier proposed the adoption of the sector theory, according to which, for any country possessing a shoreline on the Arctic Ocean, two lines pointing to the North Pole were traced respectively from the most western and eastern points, with everything falling within this pie shape pertaining to its jurisdiction. Laurier officially rejected the idea, but at the time, on several Canadian maps of the Arctic, the borders appear defined according to the sector principle.

The United States rejected this theory — there is no island to the north of Alaska — and considered the High Arctic as a terra nullius, that is, not belonging to any country. However, Russia and Norway adopted the sector theory.

Petroleum and territorial claims

In 1968-69, the discovery of significant quantities of petroleum in Alaska was to alter the course of history in the Arctic. To enable development to occur, the U.S. and Canada were going to have to settle the issue of aboriginal titles as well as their differences over the marine frontiers of the Beaufort Sea and the use of the Northwest Passage.

The discovery of oil in Prudhoe Bay on the Arctic coast of Alaska had the Canadian oil companies drooling in hopes of making similar discoveries in the Beaufort Sea and the Mackenzie River delta. 1968 was also the year of Trudeau’s coming to power. It was the end of the “goodwill” policy with the United States and the emergence of a new Canadian nationalism, which would also be expressed in the Arctic. Gone was the time when the United States could consider its differences with Canada over the Arctic as a domestic issue that could be settled among civil servants. The Trudeau government would make these political issues.

The first challenge occurred in October 1968, when Humble Oil announced that its tanker converted into an ice-breaker, the SS Manhattan, would try to cross the Northwest Passage. Instead of prohibiting access to these waters, Canada proclaimed its right to control pollution in the Arctic waters, invoking its responsibility to uphold this fragile environment and ensure respect for the indigenous peoples who inhabit it. The fact that the two U.S. icebreakers accompanying the SS Manhattan needed assistance from a Canadian icebreaker, and that the Manhattan struck an iceberg, gave some credibility to the Canadian approach.

In 1970, the Trudeau government tabled two bills in the House of Commons. The first, Bill C-202, entitled the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act (AWPPA), created a zone of 100 nautical miles over which Canada would have authority to apply its anti-pollution regulations. The second, Bill C-203, amended the Territorial Sea and Fishing Zones Act to extend the limits of the territorial waters from three to 12 miles.

President Nixon immediately reacted by announcing that he was reducing the import quotas for Canadian oil and he threatened Canada with other retaliatory measures if the legislation was adopted. Simultaneously, the SS Manhattan undertook a second voyage through the Northwest Passage, and although Humble Oil had acquiesced with the list of stipulations issued by the Canadian government, including prior inspection of the vessel by the Canadian authorities, the U.S. government refused to recognize Canadian authority over the Northwest Passage. The House of Commons replied by unanimously adopting the bills and the Canadian Senate approved them in eight days.

But before the Senate adopted the legislation the United States proposed the holding of a multilateral conference on the Arctic waters, based on their priorities. Canada was invited to participate, but was not consulted on the list of invited countries or on the agenda. Ottawa lobbied actively against the project and found enough allies to abort it.

On the other hand, the Manhattan’s voyage occurred without incident. A Canadian observer was aboard the vessel and it was accompanied by the icebreaker John A. Macdonald, whose captain was instructed to end the voyage if the situation so required. Canada had won a battle, but the dispute was now on political terrain.

The sector theory

[At this point, Pierre Dubuc digresses to cite at length an episode he says occurred in 1971, when Jacques Parizeau, a leader of the Parti Québécois, was summoned mysteriously to Chicago and then taken to a meeting at a Wisconsin retreat attended by leading U.S. military and diplomatic personnel. While discomforted Canadian officials looked on, the Americans questioned Parizeau as to his opinion on the sector theory, and whether a sovereign Quebec would apply it. It seems that Washington was concerned that applying the sector theory to Quebec’s boundaries might give it a claim to sovereignty over most of Baffin Island, which at the time contained the second largest U.S. air base after Thule, Greenland.

The biography of Parizeau from which this account is taken apparently does not indicate what his reply was to the Americans — although it says he reassured them that a sovereign Quebec under the PQ would be part of NATO and NORAD.[1]

Dubuc concludes:

“The United States clearly showed the Trudeau government that they were prepared, in order to counter Canadian claims on the Arctic, to lend their support to the idea of Quebec independence, if its promoters did not recognize the sector theory.”[2]

But he adds:

“In 1995, Jacques Parizeau realized that the converse situation could occur when the Crees campaigned in New York and around the world against the Grande Baleine [Great Whale] hydro-electric project. On the eve of the 1995 referendum [on sovereignty], he announced the abandonment of the project.”]

Toward self-determination

In 1976, the U.S. courts recognized a form of self-government for the Indigenous peoples of Alaska, after six coastal villages with a population of 6,000 joined together following a referendum. Immediately, the new entity levied a tax on each barrel of petroleum produced. The money was used to improve the living conditions of its inhabitants, but also to finance the first meeting of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), held at North Slope, Alaska, in 1977.

In 1983, during the third general meeting of the ICC, the United Nations recognized the organization as an NGO and later the ICC played a key role in drafting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The ICC promotes the right to self-determination as a means of protecting the environment.

In 1979, following a referendum, the Greenlanders obtained Home Rule, a status of self-government. At the time, that was the most advanced form of self-government granted to a predominantly indigenous population.

In Canada, the indigenous relied on the recognition granted to them in Pierre Trudeau’s 1982 Constitution to demand what would become Nunavut. Section 35 of the Constitution Act confirms the recognition of indigenous rights, which allowed the Inuit to negotiate instead of having to resort to the courts. An agreement in principle was signed in 1990 and finalized two years later after a referendum was held in which the population approved by 85% the redrawing of the boundaries. On April 1, 1999, the Parliament of Canada adopted the Nunavut Act. In 2008, when a protocol was signed on the devolution of powers, it was obvious that they were heading toward provincial status.[3]

In 1997, the Inuit of Quebec resumed negotiations for the creation of Nunavik on territory formerly known as Nouveau-Québec, covering about 507,000 sq. km., a third of the territory of Quebec. The administrative centre for the population of about 11,000 persons in Nunavik is Kuujjuaq. The region is managed by the Kativik Regional Administration, created by the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. An agreement was signed on December 1, 2006, creating the Nunavik Inuit Settlement Area, which includes 80% ownership of Quebec’s offshore islands and waters, with annual royalties paid by the federal government for natural resource development. On December 5, 2007, a new agreement in principle was signed. It seemed at the time to constitute a supplementary step toward the formation of a government of Nunavik. It provided for an elected, non-ethnic government under the jurisdiction of the province of Quebec. But the Inuit rejected this proposal in a referendum on April 27, 2011, because, it seems, they want an ethnic government independent of Quebec’s jurisdiction.

Some fundamental issues for the independentists

In the coming years the melting of the ice cap is going to make natural resource development possible in the Far North and Arctic. This has important implications for Canada. For example, the London Mining Company hopes to extract iron from a mine in Greenland and ship it to China via the Northwest Passage. Greenland, which already shares with Denmark the revenues from the development of its natural resources, sees an opportunity to end its financial dependence on Denmark and accede to political independence. The Charest government also wants to ship ore mined in the Far North through the Northwest Passage, and its Plan Nord provides for the construction of a deepwater port on the banks of Hudson Bay.

Nunavut and the other regional governments in Canada will be sure to pressure Ottawa for a more favourable distribution of revenues from natural resources.

The Arctic promises to be one of the political hot spots of the globe during the 21st century. Thus, while Ottawa promoted the idea of Nunavut as a means to obtaining recognition of Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic, the Inuit see it instead as a step toward accession to their own sovereignty.

Quebec is currently the major arctic province of Canada, as a mere glance at a map will show. Nunavik covers a third of Quebec’s territory. But under the Canadian Constitution, Quebec’s territory stops at the shoreline, which leads to the absurd situation that islands situated a few hundred metres offshore, and frequented since time immemorial by the Inuit of Quebec’s Nunavik, are not part of Quebec. However, these Inuit hold rights over the waters and islands bordering Quebec that were granted to them by the federal government.

The Inuit of Nunavik maintain close ties with their brothers and sisters of Nunavut and Greenland. In some articles published in l’aut’journal, André Binette, a lawyer who co-chaired the study commission on Nunavik self-government (1999-2001), has clearly described Greenland’s process toward political independence, which appears inevitable, and in particular the possible bandwagon effect on the Inuit of Nunavut and Nunavik[4] — a phenomenon the Canadian government is perfectly aware of and which doubtless is a better explanation for the deployment of military forces in the Arctic by the Harper government than the existence of a foreign threat.

André Binette wrote: “Moreover, in the public meetings that I co-chaired in a dozen or so villages of Quebec’s Nunavik and in my conversations with political leaders in that region it was soon evident that for many Quebec Inuit the dream of a single country composed of Greenland, Nunavut and Nunavik was quite substantial, and that the independence of Greenland, the creation of Nunavut in 1999, and the establishment of a future autonomous government in Nunavik were perceived as major steps in that direction.”

Added to this is the fact that the United States does not recognize Canadian sovereignty over the Arctic waters and that nothing prevents them from supporting the claims of the Inuit, just as they flirted with the Quebec sovereigntists in 1971 to counter the northern policies of Pierre Trudeau, witness Jacques Parizeau’s trip to Chicago.

The situation could become extremely complex and the Quebec independentists will have to think carefully before taking a position on the Inuit claims. Will they make common cause with the federal government in opposing them, and defend Canadian unity, or will they ally with the Inuit against the federal government, linking their struggle for the sovereignty of Quebec with that of the Inuit, within the framework of what could be a sovereignty-association? The debate is open.

[1] Dubuc writes that he is quoting from Laurence Richard, Jacques Parizeau, un bâtisseur (Montréal: Éditions de l’Homme, 1992). A very similar account of this meeting is found in the major biography of Jacques Parizeau by Pierre Duchesne, Tome I, Le Croisé (Montréal: Québec Amérique, 2001). However, Duchesne dates the meeting in 1969, as does Jean-François Lisée, in Dans l’oeil de l’aigle. Washington face au Québec (Montréal: Boréal, 1990). And Duchesne reports that Parizeau told his questioners that “he was in full agreement” with the sector theory (pp. 595-96).

[2] For a less sanguine interpretation of US views of a sovereign Quebec, see Anne Legaré, Le Québec otage de ses alliés: Les relations du Québec avec la France et les États-Unis (Montréal, 2003). Legaré represented the Parti Québécois government in New England and in New York and Washington from 1994 to 1996. She quotes (p. 26) a statement by Parizeau himself, in his book Pour un Québec souverain (Montréal: VLB éditeur, 1997), on the obstacles the United States posed to Québec sovereignty: [Translation] “While, in the Department of Commerce in Washington, the State Department and the National Security Council of the White House, they readily agreed that Quebec could not be excluded from NAFTA, from there to recognizing Quebec as a sovereign country there was not only a step to be taken but an abyss to be crossed.”

[3] The actual chronology differs from this account. According to the National Library of Canada,

“An agreement-in-principle was finally reached in 1990, a final version of which appeared in December of 1991.... It was then put to a plebiscite in October of 1992, and saw a record turnout of voters. The Agreement passed the plebiscite with an overwhelming majority of 84.7%. Once past this hurdle, matters moved quickly. The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act, ratifying the agreement, and the Nunavut Act [laws.justice.gc.ca/en/N-28.6/index.html], which created the new territory, were both passed on June 10, 1993....

“As with the ratification of the Nunavut Act in 1993, the actual birth of Nunavut on April 1, 1999 became an international news story. Parties, speeches, fireworks, traditional Inuit games and dances, and other activities marked the occasion.”

[4] See “Scottish, Québécois reactions to Greenland’s vote for autonomy”.

Friday, September 2, 2011

Daniel Tanuro: The Delusion of Green Capitalism

Further to yesterday’s post, “Foundations of an ecosocialist strategy,” here is an interview with the same author, Daniel Tanuro, based on his book, soon to be published in English. Its working title, I am informed by the publisher Resistance Books (U.K.), is The Delusion of Green Capitalism. The translated interview, with my introduction, was first published in January 2011 on Ian Angus’s excellent blog Climate & Capitalism.

Introduction

Daniel Tanuro’s new book, L’impossible capitalisme vert, is a major contribution to our analytical understanding of ecosocialism.

Tanuro, a Belgian Marxist and certified agriculturist, is a prolific author on environmental history and policies.

Addressed primarily to the Green milieu, as the title indicates, this book is a powerful refutation of the major proposals advanced to resolve the climate crisis that fail to challenge the profit drive and accumulation dynamic of capital. Much of the book appears to be a substantially expanded update of a report by Tanuro adopted in 2009 by the leadership of the Fourth International as a basis for international discussion. That report was translated by Ian Angus and included in his anthology The Global Fight for Climate Justice.

Tanuro’s book includes much additional material elaborating his central thesis that climate degradation cannot be dissociated from the “natural” functioning of capitalism as a system and that a valid “emancipatory project” to confront and overcome the impending crisis must recognize natural constraints and aim for a fundamental redefinition of what we mean by social wealth.

Among the topics of particular interest to readers are extended critiques of popular writers on climate crisis ranging from Jared Diamond to Hans Jonas and Hervé Kempf, as well as his critical assessment of the contributions of Marxist writers such as John Bellamy Foster and Paul Burkett. Tanuro makes a compelling case against many ill-conceived nostrums such as the Sierra Club’s campaign for immigration controls, or such cost-efficiency based market mechanisms as carbon trading and ecotaxes.

A major feature of the book is its cogent explanation of how Marxist value theory explains the ecological crisis and points to its solution. He also addresses what he considers a major deficiency in Marx’s ecology, an inadequate appreciation of the crucial implications of capitalism’s reliance on non-renewable fossile-fuel resources. This aspect is explored in detail in Tanuro’s article “Marxism, Energy, and Ecology: The Moment of Truth,” published in the December 2010 issue of Capitalism Nature Socialism.

We hope that this outstanding book will soon be published in English and other languages.

In the following interview, Daniel Tanuro outlines some of the major themes in the book. My translation from the French, À propos du capitalisme vert.

—Richard Fidler

* * *

Concerning Green Capitalism

Daniel Tanuro, you are the author of L’impossible capitalisme vert, published by Les empêcheurs de penser en rond/La Découverte. You are also the founder of the NGO “Climat et justice sociale.” What is “green capitalism”?

D.T.: The expression “green capitalism” may be understood in two different ways. A producer of wind turbines may boast that he is engaged in green capitalism. In this sense — in the sense that some money is invested in a “clean” sector of the economy — a form of green capitalism is obviously possible and quite profitable. But the real question is whether capitalism as a whole can turn green, that is, whether the global action of the numerous and competing capitals that constitute Capital can respect ecological cycles, their rhythms, and the speed by which natural resources are reconstituted.

That is the sense in which my book poses the question and it answers in the negative. My main argument is that competition impels each owner of capital to replace workers by more productive machines in order to achieve a superprofit greater than the average profit.

Productivism is thus at the heart of capitalism. As Schumpeter said, “a capitalism without growth is a contradiction in terms.” Capitalist accumulation is potentially unlimited, so there is an antagonism between capital and nature, as the latter’s resources are finite. It may be objected that the productivity race leads capital to be increasingly resource efficient, as expressed for example by the observed decrease in the quantity of energy necessary for the production of a percentage point of GDP. But this tendency to increased efficiency obviously cannot be prolonged indefinitely in a linear way, and empirically we find it is more than offset by the growing mass of commodities that are produced. Green capitalism is therefore an oxymoron, like social capitalism.